Corbin Cash Distillery

By Meghan Swanson

David Souza, a California farm boy, found his way to Las Vegas at the age of twenty-eight; old enough, he says, to have his ‘wits about him’, but certainly not too old to dream. Soon enough, he had started his own event promotion company and bought a couple of restaurants. “I was looking for something fun…I was looking for something new and exciting to be 100% mine.” he says. Selling bottle service for $600-$700 a night through his promotion company for the big-name vodka brands had him considering another new creative business pathway. “Dude, we should be selling our own brand of vodka.” he recalls thinking. “I knew at that point I wasn’t going to be making Vegas my home.” he explains. He sold his businesses and headed back to the San Joaquin Valley, where the Souza family has been farming for five generations.

“Can this even be possible? Because nobody was making sweet potato alcohol.”

David’s great-grandfather emigrated from the Azores, Portugal’s mid-Atlantic archipelago of subtropical islands, to the United States. He landed in Boston in 1917, and it’s no wonder he soon found himself on a train bound for California; the warm climate and fertile farmland may have reminded him of home. He landed in sunny Santa Cruz, spent some time working in a silver mine, and eventually settled his own farm in Atwater, California, located nearly smack-dab in the middle of the golden state we know today. Great-Grandpa Souza started out with sweet potatoes and Merced Rye.

Fast-forward nearly a hundred years, and David knows sweet potatoes. He also knew how beverage alcohol fit into the entertainment industry, and envisioned his own spot on every bartender’s shelf in America’s entertainment mecca, Las Vegas. “I told my buddies, give me a year, I’m going to make the world’s first sweet potato vodka, and then we’re gonna turn around and we’re gonna sell it in Vegas.” he recalls. That timeline eventually spooled out into a three-year undertaking, beginning with David teaching himself how to distill from an old whiskey book he found on the internet.

“It was a lot of just trial-and-error, hands-on, really, just diving in.”

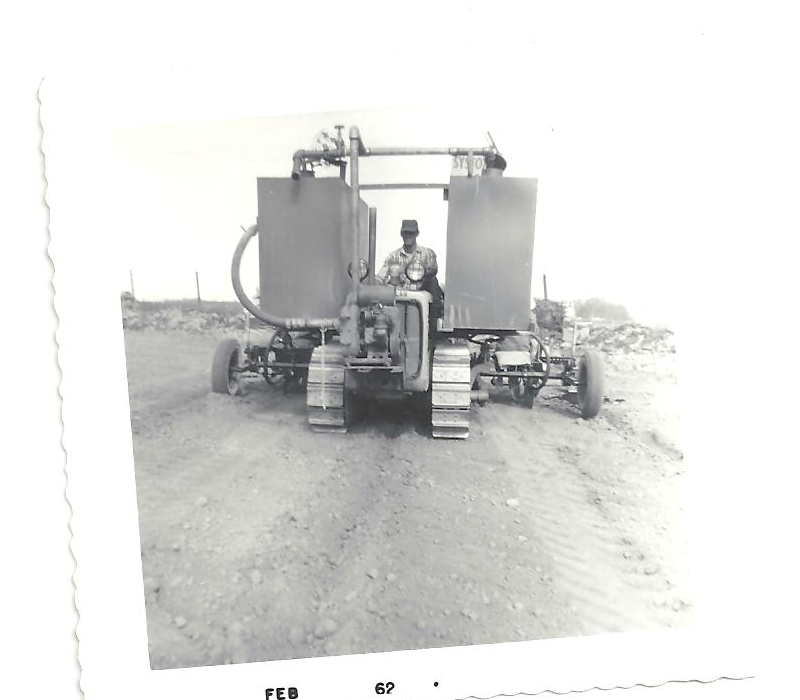

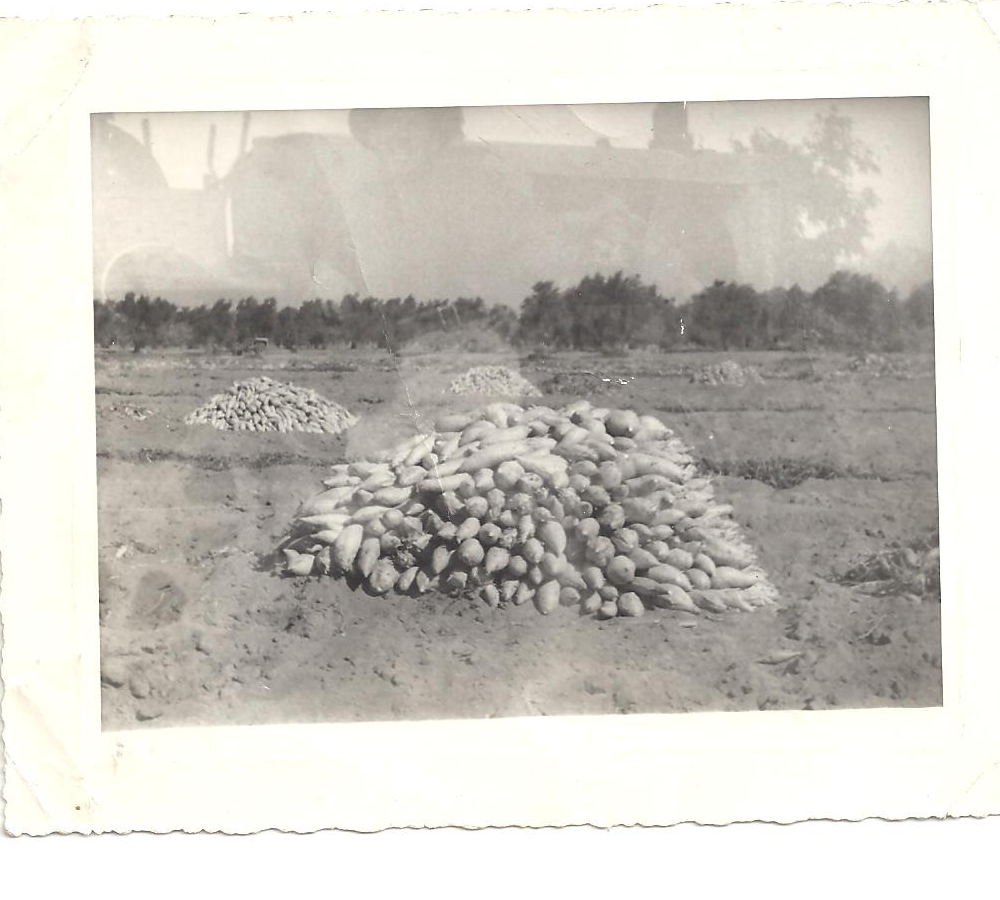

David put his first still together from parts bought online, beginning with an old beer keg. The old whiskey book was only helpful to a point–after all, he was just trying to learn to make vodka. In 2007, when his distilling journey was starting, craft distilling wasn’t nearly as prevalent as it is today. The early internet didn’t offer as much as it does now, either; the first mention of distilling sweet potatoes David found was a paper he discovered in the library. Someone in Louisiana had experimented with trying to make fuel alcohol from sweet potatoes, and concluded that the low yield made the endeavor too expensive. “Sweet potatoes, to give you an idea of why they’re so expensive…you kind of double-crop.” David explains. Tiny sweet potatoes from a previous crop are the ‘seeds’ for a new crop; those are planted inside protective hoop greenhouses in winter, and when they’re ready, they’re taken out and planted by hand in the fields. There ends up being around 12,000 plants per acre, and each plant then produces anywhere from two to ten additional sweet potatoes–which must all be picked, and packed, by hand. This translates to a lot of manual labor that still must be done by human beings, and although the farm has become more automated over the years, the Souzas still employ around 200 people every harvest.

David pressed on, digging up some beer recipes and a regular potato vodka recipe to try out. The potato vodka recipe worked, but production was low. “What I learned…was, sweet potatoes - why they’re healthy for diabetics. The complex carbohydrates, your body doesn’t break them down; well, neither will yeast, apparently.” David explains with a laugh. By chance, he ran into someone from a company that produced and sold commercial enzymes. Armed with a box of a hundred different enzymes, David tried them all out, finally finding one that cracked the code after taking a year to perfect his recipe.

The actual distilling wasn’t the only challenge David faced; like many craft distillers around the United States, he also had to get through the labyrinthine local, state, and federal regulations surrounding the production of alcohol in a post-Prohibition world. He went into the process with full transparency, meeting with a wide array of officials from his county. “I get a call, and they’re like ‘Yeah, you know, we just don’t know what to do with you’.” he remembers. He had pitched his new business as a ‘micro-distillery’; “The word ‘craft’ didn’t really exist then.” he points out. The closest comparison they had was E & J Gallo Winery in Modesto - there were no distilleries at all nearby. The county sent two of their people out to investigate; those two county employees happened to be on the younger side, and they instantly liked David’s idea. “We see the vision, and we [the county] need this.” David quotes them. They recommended that instead of seeking a conditional use permit, David go with a more vague ‘home-based business’ application. One week later, he had his business license in hand. “If it wasn’t for those two young guys coming out, who thought ‘Oh man, this is super-cool, we need this,’ I’d probably still be sitting in legislation with them trying to figure out what to do with us.” he recalls with gratitude.

In 2010, David launched his High Roller sweet potato vodka. It came in heavy, knurled, Italian glass bottles with a high silver cap–stamped with a die in honor of David’s favorite game, craps. When he applied to the TTB to open his distillery, he went after every permit he could get; a still license, a Type 4 license that would allow him to manufacture liquor, and a Type 7 license allowing for the rectification and sale of liquor directly to retailers, bars and restaurants. He got them all - and about 8 days before he opened his doors officially, an inspector stopped by with bad news. He couldn’t have both a Type 4 and a Type 7 license; he was going to have to choose. David agonized, but ultimately went with the Type 4 so he could continue to make his own product–that was the entire point of the venture, after all–but it would mean he could no longer legally sell his vodka to consumers at his distillery.

David needed distribution, and in the early 2010s, there were two big fish on the California distribution market. Unfortunately, they rarely carried craft distillates, and if you weren’t in their channels, most bars, restaurants, and shops wouldn’t carry you either. This forced David to keep the product hyper-local, relying on a cooperation with a nearby fellow distiller who had the Type 7 license David couldn’t have. “You have a seven!? I’ll make your whiskey, if you can sell my vodka!” David remembers pitching the relationship. He and Coldhouse Vodka out of Modesto would maintain this arrangement through the first two years of business. “Our Vegas plan never really worked out because of the distribution channel.” he explains. Now, however, he knew how to distill and he had all the infrastructure he needed. “I made the world’s first sweet potato vodka, I wanted to make the world’s first sweet potato whiskey.” David tells us.

“It’s a challenge being a craft spirit, but then to be something completely off-the-wall different? It makes it twice as hard, if not three times.”

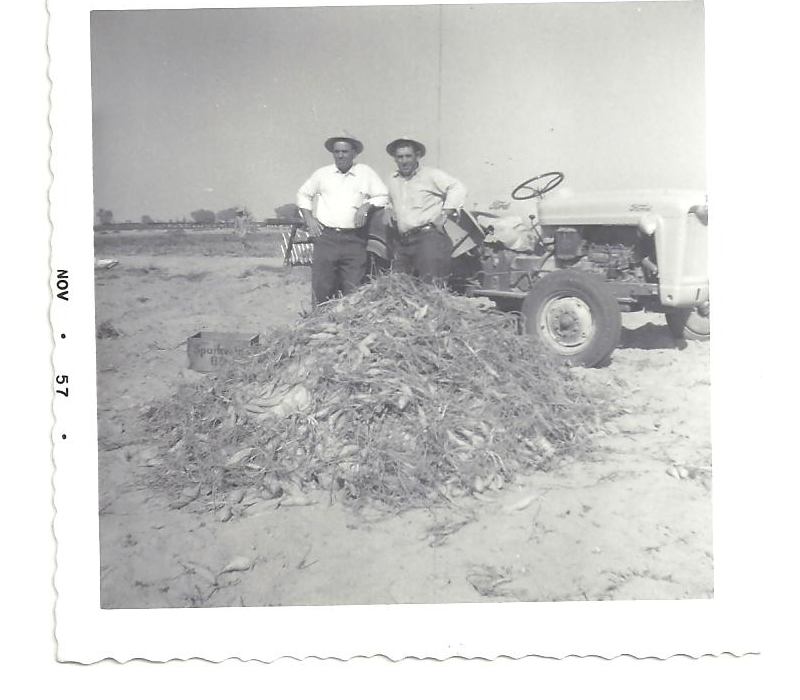

Having conquered the challenge of sweet potato vodka, David was ready to branch his interest out into other spirits. It was natural for him to turn to the other crop the Souzas had been growing for nearly a century: rye. Two seasons into the original farm, Great-Grandpa Souza had planted Merced rye as a cover crop. “The main thing with Merced rye, why it works really well here when others don’t, is that it’s really drought-tolerant.” David explains. This was a good thing back in 1917 when irrigation wasn’t readily available, and is a good thing today as California continues to grapple with a lack of water. While its starch content tends to be lower than your average Midwestern or Canadian rye, it also has a less spicy taste, lending itself to a longer finish with sweeter, chocolatey notes. David started distilling the rye they’d already been growing on the farm, laying down some barrels of rye whiskey. He also put a sweet potato distillate in barrels to age into what–he had thought–would be called sweet potato whiskey.

American craft distillers are constantly pushing the envelope, poking at the edges of the TTB’s legal definitions and agitating for new categories, such as American Single Malt. Unfortunately for David, however, the TTB didn’t agree that he had made sweet potato whiskey - at least, they didn’t agree that he could call it that on the bottle. “Rejected - you can’t call it whiskey, it’s from sweet potatoes. It has no grain in it.” he sums up their decision. This wasn’t the first time he’d tangled with the TTB over language. They had balked at his sweet potato vodka as well; they believed consumers might be confused, thinking they were buying a sweet potato-flavored vodka. David had to provide multiple examples of vodka bottles advertising the vegetation the distillate was made from: ‘wheat vodka’, ‘potato vodka’, ‘rye vodka’, and so on. He eventually won the right to describe his product as sweet potato vodka on the label. “After going through that, I was like, ‘You know what? I’m not gonna give up.’” he tells us.

David found a distiller in Colorado who had made potato whiskey - and had been allowed to call it that on the bottle. When he presented the TTB with his triumphant evidence, he was met with a surprising answer. That had been a mistake, a fluke, they said–and if David insisted on pressing his case, they’d have to go pull that distiller’s permission to use the description on his label, forcing them to pull their product off the market. “I couldn’t do that to them,” David says, so he dropped the fight. The TTB’s suggested alternative name for David’s product was ‘specialty distilled spirit’. “I learned a lot about branding and imaging in Vegas.” David says. He knew that ‘specialty distilled spirit’ products didn’t exactly have their own shelf at the liquor store. His solution would be to pivot - he would take that barrel-aged sweet potato distillate and add spices and flavors reminiscent of the baked sweet potato squares his mother made, transforming it into a cocktail-friendly liqueur. As the next-closest category to the ‘specialty distilled spirit’, it would have a more familiar place in the consumer’s mind; and a liqueur was legally allowed to go down to just 2% sugar, ensuring David could keep it not-too-sweet.

He applied a similar flexible mindset to finding a way to get his sweet potato distillate into a bottle where he could legally call it whiskey. “Believe it or not, you can put 80% neutral spirit in a ‘blended whiskey’.” he explains. So he did just that - Corbin Cash’s blended whiskey is a combination of whiskey made from the Merced rye and the sweet potatoes grown on the Souza family farms. Bartenders loved the unique sweet potato liqueur, but the blended whiskey proved to be a bigger challenge to market. It was his farm-to-bottle philosophy that ended up introducing more fans to Corbin Cash. “We’re just trying to be everything off of our farm, and this was the closest thing that I could get to a bourbon.” he explains. David knew people liked his blended whiskey–it sells very well at the distillery itself–he just had to get it out there onto more palates. “You’ve just got to find your people. What drew people to the Pet Rock? That guy sold that for like a few million bucks, right? People believed in whatever that was.” he laughs. He found his first big market in San Francisco. “The fact that we were farm-to-bottle, that was the hook.” he explains. “We’ve always been farm-to-bottle because we have a farm. Now there’s a lot more of us, but when I started, there was about three or four of us in the country.” he recalls. That uniqueness was hot in the Bay Area, and helped Corbin Cash spread to other markets as well.

“The guys were here the week before putting it all together, then we cooked, the spirits came off the next week–and so did he.”

Some distilleries come up with their branding and marketing as they go - others have a clear vision for the brand in mind from square one. David is one of the latter. “Before I did anything, I had the whole branding put together.” he says. He applied the same strong vision to another, even more personal facet of his life: his son’s name. He had always wanted to name a son Cash, after Johnny Cash. Some friends and family expressed skepticism at the idea; did he really want to name his child Cash? David certainly did, until one day a song came on the radio that he just really dug. The artist’s name was Easton Corbin. Corbin Cash, he thought - it was perfect.

The son in question hadn’t yet been born, but he and the distillery were both on their way. David had been cautioned by an attorney to just forget putting the Souza family name on the bottle–it was far too similar to Sauza tequila and likely to get him in copyright trouble. In a move nearly the opposite of many distilleries’ choice to name their product after an ancestor, David decided it would be named for a Souza descendant instead. “The name came first,” he explains, “And the kid and the whiskey were actually born on the same day. When we built the new distillery, he was literally born the first day the spirits rolled off the new still.” he recounts. “I had to call my general manager at the time, ‘Hey, his [Corbin’s] mom’s water just broke, we gotta get to the hospital, can you come finish distilling? Just watch the still.’ We literally had just started it. It was crazy.” he recalls, smiling.

In a nod to his ancestors, David did end up putting a modified version of the Souza family’s Portuguese coat of arms–shields quartered with castles–on the label. The name Souza had to go, for the aforementioned copyright reasons, and when they shrunk the crest down to fit on the bottle, the castles became indistinct blobs. As a nod to their American roots, David swapped those castles out for the proud profile of a bald eagle. A designer based in Oregon helped perfect the font on the label, and the custom, Italian glass bottles that had once been meant for the High Roller vodka brand became the vessels for Corbin Cash spirits. To this day, there’s a little hidden easter egg underneath each tall, knobby bottle: a die, molded right into the glass. It might not be called ‘High Roller’, but David wants his customers to know they’re getting the top shelf with Corbin Cash. “I don’t want to play in the cheap space. I’ve always wanted to play in the premier or luxury space. But I don’t want to be trying to sell overpriced spirits...I was reading this article about the new generations, especially Millennials, trading in their fancy stuff for new experiences that they can share.” David explains. “I feel like that’s our brand…We have a luxury bottle, good product inside, and it’s definitely the price point of shareable.” he says.

“It’s probably what gave me the confidence to try new things, because I have done so many things. Not that I'm a master at any of them, but I definitely know how to do a lot.”

David started his farming career working in the family’s watermelon fields. By age ten, he was driving tractors. At fifteen, he was given his own five acres to manage, with his grandpa’s help. In essence, he’s been managing his own business since then. “When you grow up in that environment, you kind of think everybody does that.” he says, quirking a smile. “It teaches you so much, growing up on a farm. I learned how to weld, how to do plumbing, how to do electrical work…those are things, we don’t do as much of that anymore, but I want to find a way to get my son involved in that as well because it’s so helpful when you get older.” he asserts. Farm work also taught David that a value can’t be placed on the help of others. “Our employees are like family to us; our average employee has been with us over 35 years.” he reveals. “They’re our lifeblood. Without good employees, our farm doesn’t run.” David says. “You can put the business first, but if you don’t put the family first you don’t have a business.” he finishes.

Corbin Cash Distillery’s identity as a family farm first is clearly evident when you ask David about being a farm distillery. There’s a reason he refers to their work as ‘farm-to-bottle’. “Honestly, any distillery is ‘grain-to-glass’...MGP is ‘grain-to-glass’. They take grain, they make it into spirits, those spirits are aged, they go into a glass.” he points out. The farm, and what they can and can’t do with it, dictates everything about Corbin Cash Distillery’s spirit portfolio. “We get constant aging here.” David explains. Humidity is low, temperatures don’t drop below freezing in winter, and summers can bring 110+ degree heat. “The first six year barrel I tasted…the average Joe probably wouldn’t have noticed the bitey-ness, but I did. So I took the barrel apart and chopped it up and we looked at it, and really what was happening was with our 110-112 degrees, the charcoal is spent. That’s when I realized we have got to circumvent this somehow.” David explains. “There was a point when I thought we weren’t going to get older than that. I thought “Man, we have this arid climate, we’re not going to be able to get older than six years.’” he confesses. Fortunately, they were able to apply the same aging techniques they use on their sweet potato crops. Through temperature and humidity control in their rickhouses, they have satisfactorily aged a ten-year whiskey. David hopes to release that soon, but due to a glass shortage, “it might be a 12-year before we get it out there.” he quips.

The climate has also affected how they treat their yeast. “In the beginning I really didn’t know any better, so I found a lot of beer recipes and looking at what breweries do, it’s all closed-top [fermentation]. It makes sense because they can’t have the infection, right? Because you’re drinking that final product.” David explains. As his knowledge and skills grew, he discovered open-top fermentation was absolutely an option. However, it can prove challenging when a distillery is making a rye whiskey. “There’s a thing called the ‘rye monster’, and when that stuff foams, if you’re an open-top…we’ve left the lid open in the tank and had it foam over quite a few times…and what a mess.” he says with a shake of his head. Today, they keep their fermentation 100% sealed and temperature-controlled, which they’re happy with. “We’ve finally dialed in where production and flavor profile has gotten better.” David says.

“I was kind of like, ‘who’s going to come out here?’. We’re in the central valley, we’re not in San Francisco, we’re not in L.A.. We’re in the middle of nowhere, and I really didn’t think we’d get any business.”

It was 2018 when David’s friends in the industry started to encourage him to open a Corbin Cash Distillery tasting room. He was skeptical at first, but a clear correlation between tastings at BevMo and rising sales had him changing his mind. “We saw how the tasting business really blew up our brand for sales. Taste it, they bought it.” he recalls. When BevMo’s sales strategies began to steer away from craft distilling and they dropped all but Corbin Cash’s vodka from their shelves, David knew it was time. He opened a new tasting room in 2019, gaining back some of that revenue and enjoying growing success, especially later in the year. They rented the space out for holiday parties, and then shut down in January 2020, planning to build out a full cocktail bar and open back up in a bigger space. In March 2020, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic shut the world down. David rolled with the punches. “Alright, we’re just going to go a little deeper. We’re going to build out a concert venue, we’re going to have a stage, when this thing opens up we’re just going to have a full venue.” he determined. In June 2020, once outdoor activities were allowed, Corbin Cash Distillery opened a 2-acre outdoor music venue. “Because we were outdoors, we were the only place open. We were just inundated with business.” David tells us. “COVID did not hurt us, it definitely helped us.” he says.

While COVID didn’t have a destructive effect on Corbin Cash Distillery, they are still facing an even bigger threat: drought. “Water, it’s our biggest challenge right now. That’s why it’s huge for us to be conservative with our water and figure out, what’s the future look like?” David tells us. Scarcity of water is part of the reason he made a 100% rye whiskey, instead of a blended mash bill or one made of a wholly different grain. “Going back to the fact that we just wanted to make everything off our farm; and I didn’t grow malt.” he shrugs. He is not opposed to growing other grains, and in fact has grown wheat and oats before. However, those aren’t crops that make sense in the current water situation. “It really just comes down to rainfall. Right now, if we ever start getting more rain again, we definitely would start planting other crops.” David assures us. “We know the rye will grow even in the worst case scenarios with very little water. Oats, barley, all that stuff–ain’t gonna do anything.” he explains.

Corbin Cash Distillery conserves water by using the same water that cooled the condensing unit to cook the mash; they also are fortunate to have some artesian wells on the property David’s great-grandpa settled over a century ago. David, however, is interested in seeing more reservoirs built to catch rainwater. “When we do get rain, part of our problem out here is environmentalists have stopped building new dams. There are some reservoirs that could be expanded, so when we did get heavy rain we could collect enough water for ten years’ worth of farming in our valley–but they won’t let us build those anymore.” he tells us.

Looking ahead seems to be a trait that runs in the Souza family. David describes Corbin–the actual kid, not the distillery–as a thinker. At the time of this writing, he had recently turned twelve years old, and already handles a variety of work around the family business. He can drive a tractor, a forklift, and a backhoe (reportedly, he’s better with the backhoe than even David is). “He’s definitely a country kid, which makes me happy.” David remarks with a smile. Though Corbin doesn’t spend as much time on the farm as he does at the distillery–equipment has advanced since David was a kid, and is more dangerous than it used to be–he is clearly thinking about both. David runs the distillery, while his father takes the lead on the farming side of things. Corbin recently asked David, “Dad, how am I going to run the distillery and the farm someday?” Fortunately, Corbin has plenty of time to figure that out while his highly adaptable dad is at the helm.

“I fell in love with it after I left. After I spent a lot of time in Vegas with other businesses, and I’m like, ‘Actually I miss that life.”

From rollin’ high in Las Vegas to rolling through the fields on a tractor, David Souza has experienced a lot of life. Like his great-grandfather before him, it turned out to be a good thing for him to journey away from home and try his hand at something new. His radical vision of turning the humble sweet potato into a shining bottle of luxury for the denizens of Las Vegas led him down a road somewhere in between the two. Now, he takes what his family grows in their very own fields and turns it into a portfolio of farm-to-bottle spirits, ready to be shared and savored - all while giving his own son access to all the lessons and knowledge unique to family farm life. It might not be Los Angeles, but for those who want a homegrown, truly ‘craft’ and delicious taste of the San Joaquin Valley, that fact can be considered a plus.

TASTING NOTES

Merced Rye (45% ABV)

Nose: Salted Caramel, Peaches, Vanilla, Fresh Cut Flower Stems

Palate: The mouthfeel is light and a bit oily with oaky notes up front that settle into subtle sweet vanilla and butterscotch flavors. Savory hints of peanuts, bacon and black pepper emerge in the midpalate leading to a medium finish with lingering heat.

The nose on this whiskey is sweet, though there is an off-note that runs beneath it that may reveal the maturity of the product. The most interesting thing about this rye whiskey is the earthy and savory flavors on the palate.

1917 Cask Strength Rye (61.5% ABV)

Nose: Brown Sugar, BBQ Sauce, Honey

Palate: The mouthfeel is sharp and spicy with sweet notes up front of salted caramel and butterscotch. Heavy spice comes through in the midpalate, balancing out the sweetness and settling into orange, peach and oak flavors on a long finish.

We don’t usually mention this in our notes, but the color on this whiskey is beautiful. A deep amber shade that is very inviting. This is a big bold rye whiskey that delivers a complex and enjoyable drinking experience. A few drops of water can help to unleash everything this high proof whiskey has to offer.

Sweet Potato Liqueur (35% ABV)

Nose: Sweet Potato, Pumpkin, Brown Sugar, Cinnamon, Anise, Allspice, Cardamom

Palate: The mouthfeel is soft and silky. It is deliciously sweet with strong notes of sweet potato, brown sugar, cinnamon, and butter with a short but satisfying finish.

What can we say? This is thanksgiving in a glass. The flavors are exceptional and nostalgic. It’s not what we usually drink, but we would happily have this neat, on the rocks or in an inventive cocktail.