Journeyman distillery

By Meghan Swanson

An odds-defying hole-in-one. A shot launched from half-court, sailing through the hoop with a swish. A down-at-heels American town watching an abandoned building fill with light, people, and purpose again. One might call these fairytale moments, happy endings that almost never happen in real life; the key word would be almost. The world of sports is filled with incredible stories of surprising victories and perseverance that paid off, and so is the world of business. Anything, anything at all, can happen–and Bill Welter knows it. The founder and CEO of Journeyman Distillery, Welter was hooked on the golden promise of possibility at an early age. Following glimmers of it led him around the world and back again, and put his career on a trajectory he never imagined for himself when he was just another Indiana kid hitting golf balls into the cornfield across the street.

“Like a lot of young people, after I graduated from school I wasn’t quite sure what direction I wanted to go in life. One thing I did know is that when I pursued golf, it seemed to always work out.”

Welter’s father was an avid golfer, and introduced his son to the sport early on. “That was back in the day, when parents used to drop their kids off at the golf course in the morning and pick them back up at sunset,” Weller recalls. “That really was the reality, and we loved it.” He went on to play competitively in high school, and then played four years of collegiate golf at his alma mater, Missouri State University. When he graduated from college, he let golf lead him again - this time, to apply for a British work visa. Welter’s hope was to get to St. Andrews, Scotland, the home of golf and its most historic courses. “Somewhat unexpectedly, I got it–and then I had to make the decision of whether to go or not,” he explains. “Looking back now, I wonder why I deliberated,” he shares. “Twenty-five years ago, it seemed like the world was bigger. Today you can get online and see just about anything; back then, it seemed like a big deal.”

Young Bill decided to go for it, bravely hopping a plane to Edinburgh, then a train, then finally a bus. From a payphone on the streets of St. Andrew’s, he called home to Indiana. “I remember my dad picked up and I said, ‘Well, I made it.’” he recounts. His long journey was over, but his adventure was just beginning. “I got the first job I could find, which was as a dishwasher at the Old Course Hotel.” he says. One night in the dish pit, he ran into an Australian tending the bar. “He comes around the corner with some plates in his hands and he says, ‘What are you doing here?’” Welter remembers. “I said, ‘Well, I’m, you know, washing dishes.’” he laughs. “What are you doing in Scotland?” clarified the Australian.

Welter’s new acquaintance was Greg Ramsay, drawn to St. Andrews from Tasmania by the same lure as Welter: golf. Welter was working at the hotel to support himself and fulfill his visa requirements while he learned more about the beloved game, Greg was working there to fund an even bigger dream: building a golf course back in Tasmania. “He and I become good friends–lifelong friends, now–and that kind of started my foray into not only learning more about the game of golf and the history of Scotland, but the history of whiskey and why the Scots love it so much and why it’s such a great product,” Welter explains.

At the time, Welter had no concept of the finer points of whiskey. “I can tell you in college, no one was asking like, ‘What’s the mash bill?’ or ‘Where was this distilled?’. Everyone was just happy if you showed up with a bottle of whiskey. It didn’t really matter what it was or where it came from.” he tells us. “What I learned in Scotland was that they have an incredible reverence for this ‘water of life’, as they refer to it. It’s part of the fabric of their society.” he says. It was a significant shift in his view of distilled spirits, which so far had been informed only by his college experiences. “My time in Scotland left a huge impression on me, both from a golf perspective and a people perspective–the Scots are wonderful people–and of course the whiskey perspective.”

“Opening a business was both the hardest thing we ever did and the most exciting thing we’ve ever been a part of.”

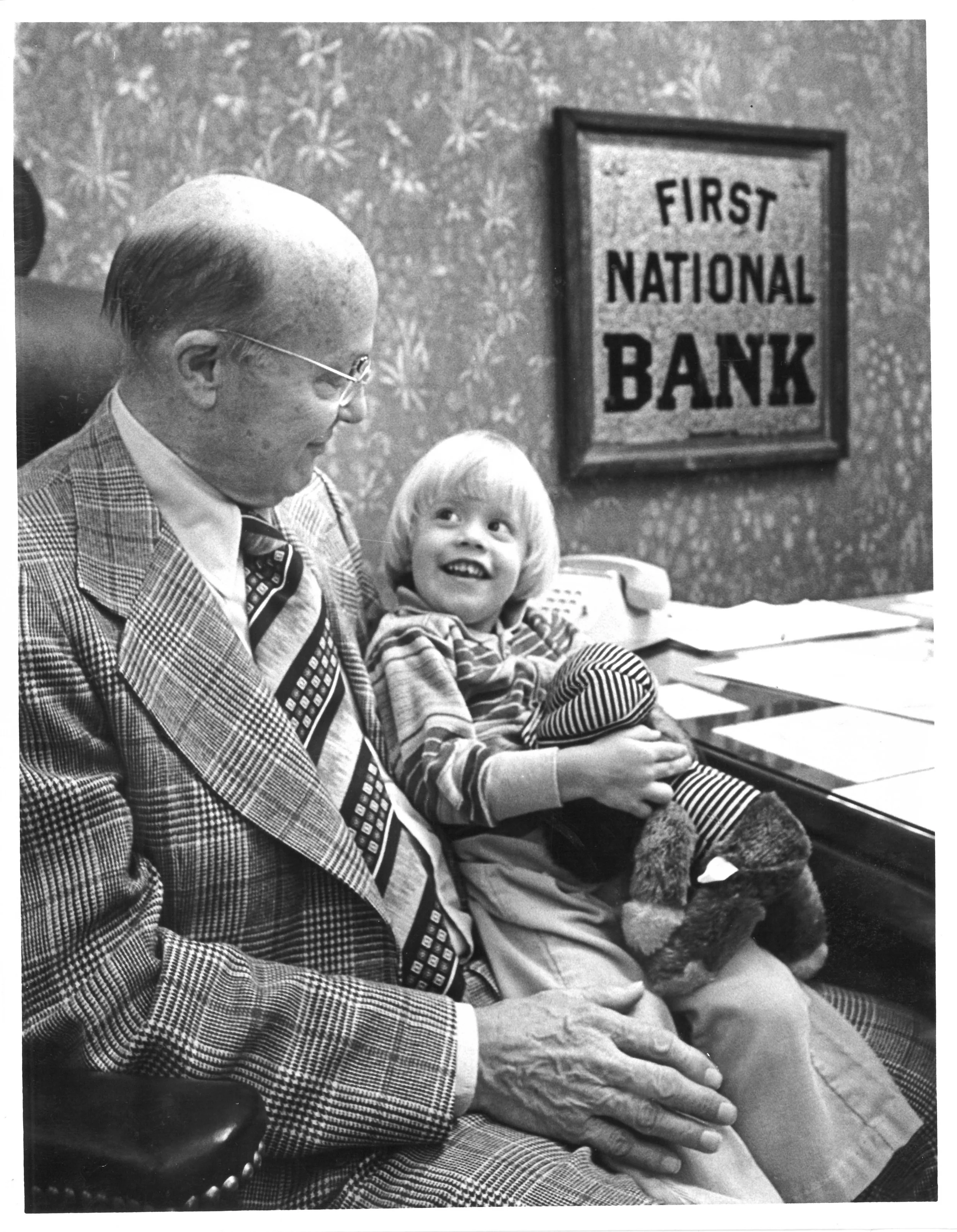

In 2009, when Welter was preparing to launch Journeyman Distilling, the craft distilling landscape looked very different from today. In a recession-ravaged economy and an industry that was unknown, he saw opportunity. “It was an exciting time; it seemed like anything was possible.” he describes. Optimism and a certain tolerance of risk are something he comes by naturally. “My dad says that when his dad, my grandfather, died, he must have jumped into my body,” Welter says with a smile. “He had an appetite for risk taking.”

When Welter’s grandfather was in his late fifties, he decided to jump into a new industry that he knew little about: banking. He bought into a small community bank in their hometown of Valparaiso, Indiana. “I think my grandfather believed in that industry, and believed in the community of Valparaiso,” Welter opines. The plan was for the bank’s former president and owner to stay close in year one, helping Welter’s grandfather learn the ropes. Unfortunately, the bank president died of a heart attack one week after the sale closed, leaving Welter’s grandfather adrift in uncharted waters. Welter’s father, enjoying a successful career elsewhere, answered his own father’s plea for help and together they worked hard to keep the community bank afloat. “[The bank] struggled considerably and really didn’t start doing well until the ‘90s, almost 20 years after he got into it…when my grandpa died, I think in ‘92, my dad felt some sense of relief that he knew the bank was in a decent position and was finally doing well when he [Welter’s grandfather] died.”

In 2007, Welter himself was working at the bank in commercial lending. “My grandpa and my dad had a long-term vision of a multi-generational business that was family owned and operated and community-based—but my dad’s siblings felt otherwise.” Welter explains. Despite their wishes and best efforts, Welter and his father were unable to prevent the sale of the bank. “One day I was working in the bank, and literally the next day I’m looking for a job.” Welter recounts. The vanishing of the family business and Welter’s career trajectory didn’t drag him down for too long, however. He rolled up his sleeves and started pursuing other work. “I think I would have been a good banker and I think I would have grown that business and we would have had some great success–but as fate would have it, my opportunities would lie elsewhere.” Welter explains.

At loose ends, Welter decided to go and see his friend Greg Ramsay in Tasmania; Greg had achieved his golf dreams in developing the Barnbougle Dunes Golf Links, and was making headway on his whiskey dreams by setting up his own distillery. Of a rarefied number of five or six distilleries in total at the time, Welter got to meet and learn from some major players: Bill Lark of Lark Distillery, Casey Overeem of what is now Overeem Whisky, and Patrick Maguire of Sullivan’s Cove. “I remember going to see Patrick at Sullivan’s Cove, and there’s this big still there and…like, the still isn’t running. There’s not a mash cooking. There’s nothing in the fermenters.” Welter recalls. During this time, Sullivan’s Cove would have been making the whiskey that would later earn them World’s Best Single Malt–to this date, the only Australian distillery to claim that honor. “And I’m telling you, this guy said to me ‘Let’s go sailing’. That was his plan for the day.” Welter says. They took a hair-raising spin on the waters of Hobart Harbor, where the boat’s guy lines were all that kept Welter from being tossed into the Tasmanian sea. “My god, I damn near went into the freaking ocean!” he exclaims. “But my time there in Tasmania, I think it gave me enough confidence to think I could do it.” Welter now knew what was next: his own foray into the world of whiskey.

“My dad is one of my biggest advocates and is a great support, but even he was like, ‘What are you doing?’”

“The idea of Journeyman,” Welter explains, “was an extension of the family banking business to create a multi-generational, family-owned and operated business that had an impact on the community.” Welter had the family support, and he had made strides on learning the distilling business with the guidance of Chicago-based master distiller Robert Bernicker of KOVAL Distillery. Now all he needed was community. “I had looked and looked and looked for quite some time, and couldn’t find the right place.” he explains. He wanted an old factory building, but not too far from Porter, Indiana where he resided at the time. One day, someone suggested he check out the town of Three Oaks, Michigan, right on the border between the two states. “I did, and drove down the main street and my eyes kind of got real big and I thought, ‘This is it.’” Welter shares.

Three Oaks is technically a village, population 1,370 as of the 2020 census, and had an abundance of charm and a perfect old factory building. Erected by a Gilded Age industrialist for the stripping of quills from turkey feathers to be used in the garment industry, it had been purchased by one man in the 1970s who had the foresight to leave all the empty buildings standing. “We were able to buy that section, my dad and I, and started our rehab [work] and brought the old building back to life,” says Welter. “Lo and behold, we had a distillery on our hands.”

Welter distilled the first batch of rye at KOVAL under Bernicker’s guidance. They produced between 300-400 gallons there, not an unimpressive feat considering the size and scale of that distillery at the time. “At the time, I think the still they had was only yielding about 10-15 gallons a run. It’s tiny, so there were quite a few mashes and distillations that occurred to achieve that.” Welter recalls. Many of these runs were accomplished in the long hours of the night, as KOVAL was using their equipment during the day. “I can even remember thinking, well, we should call this our midnight run series or midnight something or other.” Welter says with a smile. The first of what would be several names for the whiskey that would not stick.

Trademark snags challenged Welter and Journeyman in the early days; trying to name their first whiskey after Welter earned them a tangle with the Sazerac brand–Welter’s name, W.R. Welter, apparently bore too close a resemblance to the established W.L. Weller brand for Sazerac’s comfort.

When Journeyman Distillery opened its doors to the public in 2011, they had settled on the name Ravenswood Rye for their young rye whiskey, an homage to the neighborhood in Chicago where it was distilled. “Journeyman did not open to great fanfare,” Welter confesses. “When we had our opening day we had 26 or 27 people walk in the door all day–and most of them were my friends and family.” he says with laugh. “And that was in a time when, you know, in the craft brewing industry if a brewery opened anywhere, there was a line around the town to get in. And we had 26 people show up,” he reiterates.

The naming war was not over either. Welter was completely unaware of the existence of Ravenswood wine - a well-known brand whose parent company objected strenuously to the accidental infringement. Welter attempted to compromise, acknowledging the wine’s trademark dated back to 1972. They didn’t need the name Ravenswood, but could they keep the raven on the label? Welter loved the look and thought it a fair compromise. The attorneys allowed that they could keep the raven - and look forward to being sued for all the profits he earned selling the whiskey with that logo on the bottle. Welter, frustrated, gave in. He felt like the raven had been whisked away from them like a cartoon - leaving nothing but one feather drifting gently to the ground where the bird had once been. “So we renamed the product ‘Last Feather Rye’ after that experience.” he says with grim humor.

Sourced from whiskeyconsensus.com

“If you use cheap, inferior ingredients, you’re going to get a cheap, inferior product. So we did not skimp on the grain quality.”

In 2010, rye whiskey was a very niche offering; Welter describes it as a ‘totally unknown category’. Its association with America’s early history felt like a perfect fit for Journeyman. “The product dates back to the founding fathers, to a time when Americans were coming over and settling this country. Huge risk takers,” Welter points out. Although rye whiskey made up less than 1% of the market at the time, he felt drawn to it. “You can imagine people sipping on rye, and dreaming and scheming and planning what this country would end up being. I think, from a historical standpoint, rye is critical.” Welter claims.

The rye itself, and all the other grain Journeyman uses in its products, is both certified organic and kosher. “That was probably one of the easier decisions we made when we opened the distillery, among thousands of little decisions at the time.” Welter says. “We really felt and believed that if we were going to make whiskey, we were going to make it with the best grains that we could find, and at the same time support organic growers, which we thought were critical to the health and success of Americans and America’s kids.” he asserts.

One of the most special farms Journeyman sources its grain from is the Welter family’s own farm in Putnam county, Indiana. It has been in the family since the 1940s, and Welter’s father is the owner and operator. “Some of the best whiskey we’ve ever made is from the family farm,” Welter says proudly. Their Farm Series kicked off with a 100% rye that Welter maintains is the best product Journeyman has ever made. The next product was their Farm Bourbon, made with a unique mash bill of 51% heirloom red corn and 49% malted triticale. Journeyman has also experimented with popcorn grown on the farm, turning it into their intriguing Popcorn Bourbon.

Having cut his teeth on Kothe stills at KOVAL in Chicago, Welter brought that knowledge back to Three Oaks where Journeyman began with a 150-liter hybrid Kothe still. Over time, the distillery scaled up—first to an 1,100-liter, and eventually to a 5,000-liter system. “The Kothe stills were fantastic,” Welter reflects. “They gave us the flexibility to make a variety of different products, which we needed.” That flexibility was crucial in Michigan at the time, where tasting rooms could only serve products made in-house. Alongside whiskey, Journeyman quickly added vodka, gin, brandy, rum, and a lineup of liqueurs and cordials to keep the bar humming.

When Journeyman opened a second location, their Valparaiso distillery in Welter's hometown which opened to the public in 2023, a Vendome column still became the centerpiece. Today, most of Journeyman’s bourbon and rye is run through that system, while the Kothe stills in Michigan handle the rest. The newer Kothes are true pot stills with offset columns, giving the team the choice to run spirit directly from pot to condenser or to engage plates in the column for a lighter profile. With the Vendome in Indiana, the distillery can dial spirits anywhere from 130 to 190 proof depending on the style. Welter admits, “Someday, we’d love to buy a Forsythe still,” suggesting a smaller 500-liter system for a proper Scottish-style run. If that day comes, Journeyman will boast a rare hat trick of distilling systems.

On the maturation side, those first 400 gallons of rye distilled in Chicago were laid down in an assortment of casks ranging from five gallons to the industry-standard fifty-three. The experiment gave Welter a chance to see how barrel size shaped flavor. “I would say the best whiskey we’ve ever made has come out of fifty-three-gallon barrels and fifteen-gallon barrels,” he says. Over time, the distillery has shifted almost entirely to industry standard fifty-threes, though Welter acknowledges that wasn’t an option in the early years. Smaller barrels allowed a young brand to release whiskey without waiting five years for returns. “You have to use fives and tens and fifteens, and honestly, at the time, I think people understood that and expected it,” he says. Today, patience—and plenty of full-size casks—define Journeyman’s house style.

“There was a lot of excitement, a lot of joy, a lot of dreaming. When we got this thing started, the possibilities seemed like they were endless.”

Bill Welter has played a long game in the field of craft distilling; from startup with long odds that puzzled even his closest supporters to a successful multi-faceted business that boasts a second location. Perhaps Journeyman’s most unique offering, besides its award-winning distilled products, is its massive family-friendly putting green at the Three Oaks location. One of the top ten largest putting greens in the world and the largest one not affiliated with a golf course, it is also free for children. “The intent there was to create a green space in which kids had an activity where they can put away their iPhones and iPads and run around outside,” Welter explains. “Maybe some kid will pick up a putter at Three Oaks and discover he’s pretty good at it.” he says with a smile. Charmingly, the green is named Welter’s Folly.

Throwing oneself heart and soul into the business of craft distilling comes with plenty of risk - but it can also come with great reward. In the face of several challenges over the years, from trademark battles, to wastewater disputes and even the uncertainty of a global pandemic, Journeyman has met each obstacle with the same persistence that has always fueled it. Instead of slowing down, the distillery leaned into growth, opening restaurants, building event venues, and hosting everything from bustling community markets to weddings beneath the rafters of the old Featherbone factory. What could have remained a single-purpose distillery has instead become a hub of activity and connection proving that Journeyman’s success is measured not only in bottles filled, but in countless ways it has become woven into the daily life of Three Oaks and beyond. “It’s something we’re proud of, as early trailblazers in this business, taking a risk when no one was going to do it.” Welter says, “We still get people come up and say…’You are our inspiration to open a distillery, and we just wanted to say thank you’.” he recounts. In golf, whiskey, and life, each drive forward can bring rapture or ruin. While neither outcome is certain, one thing is: there is great joy to be found in playing the game.

TASTING NOTES

Featherbone Bourbon (45% ABV)

Nose: Vanilla, Orange Peel, White Pepper, Cut Grass

Palate: The mouthfeel is oily with sweet notes of bubblegum up front that are quickly accompanied by orange oil and pepper on the midpalate. There is a medium finish with lingering flavors of pepper, cinnamon, vanilla and steamed green beans.

This bourbon has the soft and sweet appeal of a wheated bourbon. The oily texture from the pot stills is very nice and differentiates it from industrial/large-scale commercial wheated bourbons. My palate is sensitive to the bubblegum flavor wheat can sometimes give off, which isn’t the most appealing to me, but I have no doubt this is a winning bourbon for many.

Silver Cross Whiskey (45% ABV)

Nose: Rose, Almond Flour, Brown Sugar

Palate: The mouthfeel is creamy and coating with sweet notes of honey and vanilla up front. Once again, the midpalate introduces some light peppery notes, along with allspice and clove. The clove persists into a long finish with floral flavors, bready flavors, cinnamon, oak and vanilla.

This was one of their whiskeys I was most excited to taste, and it does not disappoint. It is distinctive. It doesn’t taste like a bourbon, or a rye, or a wheat, or a malt. By using all four grains in equal proportion, Journeyman has created a whiskey with a flavor all of its own. Each grain brings something to the table. Sweetness from the corn and wheat, spice and floral notes from the rye, and the malt creates a bready foundation for everything to play on.

Corsets, Whips and Whiskey (58.5% ABV)

Nose: Malt Chocolate, Saltwater Taffy, Vanilla

Palate: The mouthfeel is thick and coating with sweet flavors of maple and cinnamon up front. The midpalate is strong with a burst of earthy, floral flavors which give way to pepper and baking spices before settling into a long finish with notes of salted caramel, cinnamon roll, oak and spice.

Wow. This is a phenomenal whiskey. I love the higher proof. It gives the whiskey an edge, but the thick and oily texture, along with the dessert-forward flavors, make it very easy to drink. The flavors are loud and in your face in the best way. I was a little worried about this one, given my sensitivity to wheat and that bubblegum flavor I picked up on in the bourbon, but this is a masterful wheat whiskey. This will be my go to dram of Journeyman for sure, though I hope to one day get my hands on that Last Feather Rye.